How Scouting Began

Forged in the Wild: How Kids Created Scouting

Scouting began with a boy alone in the wilderness. Everything else came later.

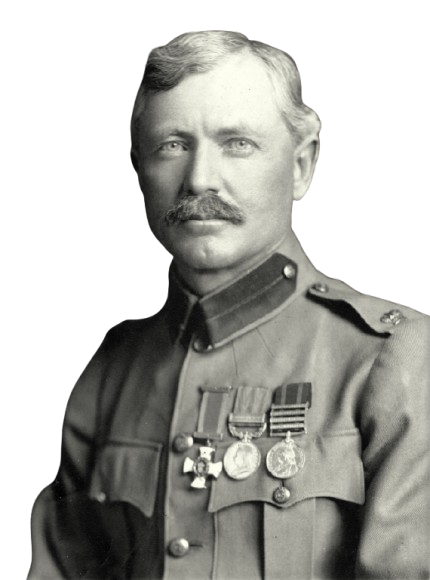

Frederick Russell Burnham was twelve years old, a Scout-aged kid, when he learned to survive alone in the Old West. No program. No handbook. Just grit, instinct, necessity, and unbridled curiosity. Mentored by Native Americans, mountain men, pioneers, military scouts, cowboys, and prospectors, he became the model for what a Scout could be, long before the word was formalized. All in a world where a man’s word was his bond. Today, we call that Trustworthy. He also modeled how Scouting would be taught: by direct trial-and-error experience in the woods. With mentors.

|  |

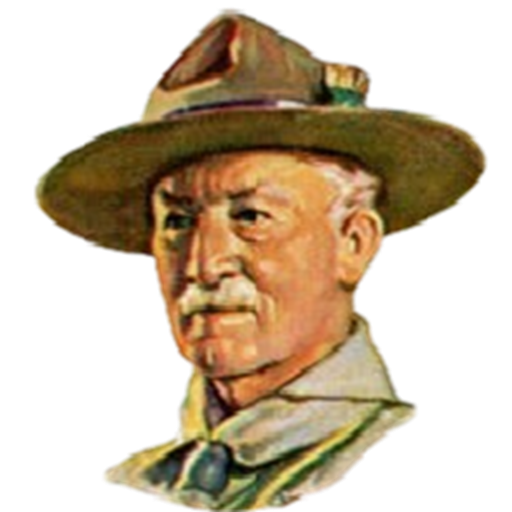

| Frederick Russell Burnham | Robert Baden-Powell |

Years later, in Africa, he trained and led British military scouts under Baden-Powell. After the war, they worked together to create a training manual for military reconnaissance. Unexpectedly, boys read it. Boys loved it. And boys began to take it into the woods and practice the skills. Not because they were told to, but because they loved the adventure. And came to love the out-of-doors.

That surprising interest by boys induced Baden-Powell to create an experiment (called Brownsea Island) to discover how boys interacted with that military material. He then created a youth version of his military scout handbook. And only then, an organization.

So Baden-Powell’s military documentation of what Burnham lived (learned in his youth in the Old West), plus his understanding of the character of his own boyhood (some childhood principles became the Scout Law), were the foundation of that first youth Scout handbook. That book was the foundation of worldwide Scouting. All derived from actual youth experiences. The entire approach was radically different than classical education methods and principles.

Scouting came to America not through policy, but through a good turn: A British Scout helped a lost man in the fog. That man was William Boyce. The rest is often told as an institutional triumph. But the real story is simpler, and more radical.

Boys bought the American Handbook for Boys, created by the BSA based on the British version. They went into the woods. They didn’t wait for permission; they formed patrols. They didn’t wait for a charter; they found someone to be Scoutmaster. They built a movement that spread like wildfire.

It was a movement by and for the boys. Any organization that claims to serve Scouting must serve that movement. Not the other way around.

Scouting as Moral Posture

Burnham’s Scouting began in the Wild West: young, alone, and untrained. But it was later tempered in the fire of war. As a military scout in Africa, Major Burnham operated beyond the reach of command. No one watched over him. He and the scouts under his command were trusted to navigate the terrain independently, assess the risks, and take action. Only a trusted man can be a military scout.

That same ethic became the blueprint for youth Scouting: self-determination, responsibility, and above all, trust. Only a trusted child can be a Scout.

A youth Scout, like his military counterpart, must not be closely supervised. If he is, the experience becomes babysitting, not Scouting. The Patrol Method collapses. Youth leadership becomes symbolic. Nature becomes a backdrop, not a teacher.

Scouting was never meant to be comfortable. It was meant to be real.

Burnham didn’t just model Scout skills. He modeled the posture of Scouting. And Baden-Powell translated that posture into an ethical system designed to grow children into responsible adults.

The Poison Pill: Charter and Control

Scouting was a movement. The Congressional Charter made it a monopoly.

Baden-Powell’s final letter to Scouters was not entirely sentimental. It contained a warning. He insisted that professionals must never run Scouting. It must remain in the hands of volunteers: those who lived the methods, not managed them. He knew what would happen if paid staff took control: the movement would become a product, and the boys would become customers.

America ignored that warning.

The Congressional Charter granted to the Boy Scouts of America in 1916 was hailed as a triumph. In truth, it was the beginning of capture. The Charter eliminated competition. It gave the BSA exclusive rights to the name “Scouting”. Other outdoor youth movements – Woodcraft, Lone Scouts, independent troops – were absorbed, erased, or sidelined.

Some who folded their organizations into the BSA later regretted it. They watched their rituals diluted, their methods standardized, their vision subordinated to bureaucracy. What had been a boy-led movement became a professionally managed brand.

The Charter didn’t just centralize control. It institutionalized drift. It made the organization the master, and the movement the servant. It replaced challenge with program. Mentorship with management. Meaning with metrics.

The BSA organization was never again accountable to the movement. Only to itself.

But the movement did not die. It retreated: into local troops, into quiet mentorship, into the hands of Scoutmasters who care. Even today, in a culture that teaches relativism and normalizes manipulation, Scouting still produces something different. Not perfectly. Not universally. But undeniably. We see it in the boys and girls who lead with sincerity. Who care about others. Who grow through challenge. The Scout Law, even weakened, still stands taller than the ethics taught in most classrooms and boardrooms.

What remains is real. And it is that remnant of the true Scouting movement – tiny, disjoint, and fought by the system – that calls us to restore, not reinvent.

Yet vast are the weaknesses of today’s Scouting compared to what I experienced as a Scout in the 60’s.